Redefining Mountaineering Greatness: Nirmal Purja and the Purist Pantheon

Sharanya RayCategory: Article

Date of Publication: Sept 8 , 2025

On July 3, 2025, Nirmal “Nims” Purja completed a feat that stunned the mountaineering world: his fiftieth 8,000-meter summit, topping Nanga Parbat in northern Pakistan. Fifty peaks above 8,000 meters - a number no climber in history had ever achieved - positioned Purja as a figure of unprecedented ambition, endurance, and logistical mastery. Yet, when measured against the ethical standards of the alpinist pantheon - Reinhold Messner, Jerzy Kukuczka, and Denis Urubko amongst others - Purja occupies a contested space. Even in April 2019, as a former Gurkha soldier, when Purja began an audacious project: to climb all fourteen of the world’s 8,000-metre peaks in under seven months, he succeeded, smashing the previous record of seven years by South Korean climber Kim Chang-ho, though without oxygen unlike Purja. But in the world of alpinism - the achievement landed differently. Was Purja’s blitz a revolution in high-altitude climbing?

To understand why, we need to step back and examine what the mountaineering community has long considered “greatness.”

Siege vs. Style: The Old Debates

Mountaineering, for all its romanticism and spirit, for decades, has been defined not just by summits reached, but by the style in which they were reached. Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay became immortal in 1953 for one summit: Everest. In 1978, Reinhold Messner and Peter Habeler shattered perceived limits by climbing Everest without supplemental oxygen - a climb Messner described as “killing the impossible.” He later accumulated 31 eight-thousander summits across his career. Kukuczka had 24. Both legends climbed oxygen-less, whereas Purja's expeditions averaged over eight 8,000-meter summits per year, including double ascents in a single season for Everest (8848m), Lhotse (8516m), and Makalu (8481m). His most significant oxygen-less summit remains the first Winter ascent of K2 (8611m) in 2021. His logistical planning ensured an 86% success rate on attempted summits, significantly higher than historical averages for Himalayan expeditions. Purja’s record invites reflection: in the age of speed, scale, and spectacle, what does it mean to be truly great on the world’s highest peaks?

The Purist Ethos and its Followers

Messner, the first to summit all fourteen 8,000-meter peaks without supplemental oxygen, often solo-ed and frequently pioneered new routes. Between 1970 and 1986, his ascents combined technical skill with existential confrontation: isolation, extreme cold, and near-constant exposure to death but Messner’s dictum was clear: “The mountain is not conquered, it simply tolerates your presence for a moment. And what matters is how you got there.” So when he solo-ed the south-east face of Nanga Parbat in 1978, it forever remained a testament to alpine-style morale. He also opened four new routes, notably the east face of Gasherbrum I, others being Everest via the North Col in 1980 solo or Nanga Parbat’s Rupal Face in 1970 - quite the benchmarks not just for physical difficulty, but for boldness of conception.

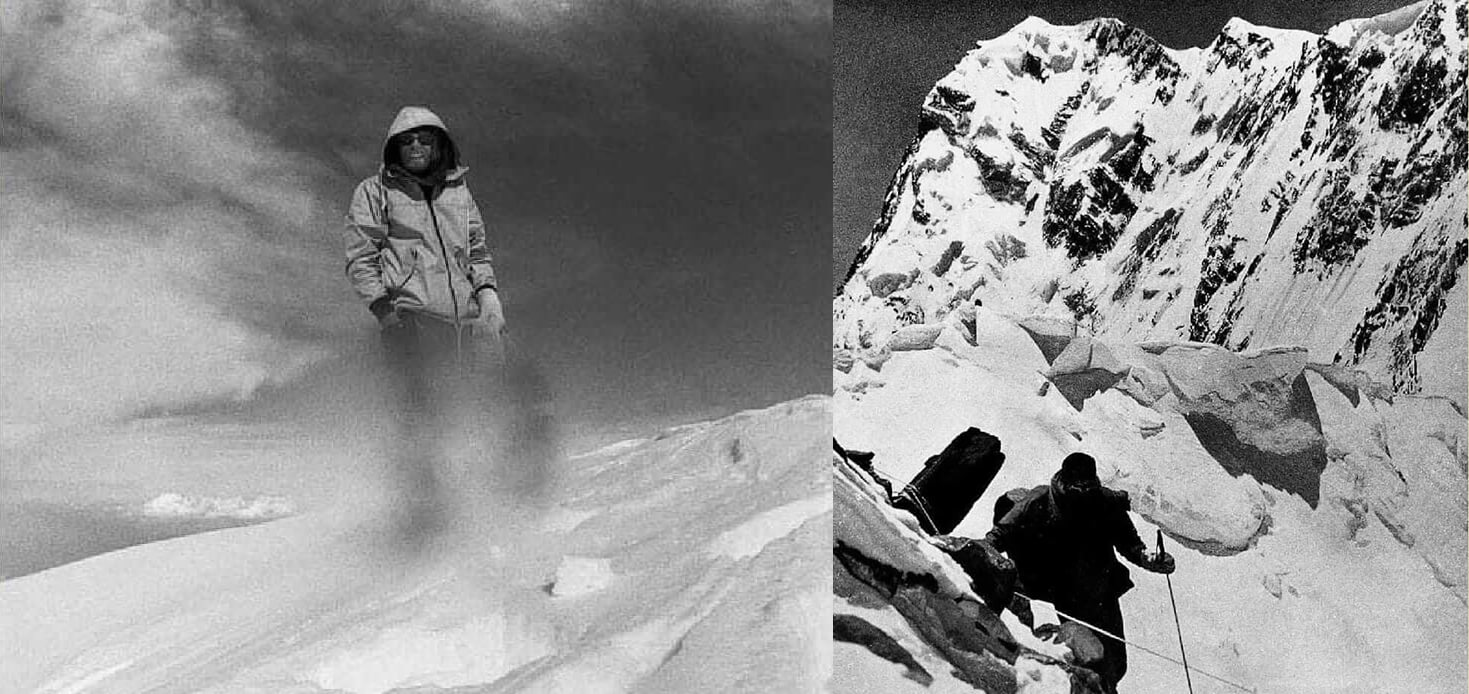

On his way to the top of Nanga Parbat (1970), with Rupal Face seen on the left. 2. On top of Nanga Parbat. Courtesy: Naked Mountain, written by Reinhold Messner

Contrast I: Jerzy Kukuczka and the Art of Suffering

Jerzy Kukuczka, the “Ice Warrior” of Poland, climbed all fourteen 8,000ers between 1979 and 1987, including four first winter ascents and other ten by having established new routes. He embraced minimal support, alpine-style climbing, and repeated exposure to extreme hazards, paying the ultimate price on Lhotse in 1989.

If Messner redefined style, Jerzy Kukuczka epitomised it. The Polish climber summited all fourteen 8,000-metre peaks in just under eight years - second only to Messner, but with a staggering caveat: most of Kukuczka’s ascents were via new routes or in winter, underfunded, with handmade gear. Consider his 1984 winter ascent of Dhaulagiri via the north-east ridge - a feat so bold that decades later, Denis Urubko called it “a miracle of willpower and vision.” Kukuczka’s 1986 winter ascent of Kangchenjunga with Krzysztof Wielicki remains one of the most formidable achievements in mountaineering history. As The Alpine Journal once noted: “Where Messner expanded the frontier of possibility, Kukuczka redrew the very map of the Himalaya.”

Jerzy Kukuczka on top of Shishapangma (1987) Courtesy: Challenge, the Vertical: My Vertical World, written by Jerzy Kukuczka

Contrast II: Denis Urubko and the Edge of Risk

Enter Denis Urubko, the Kazakh alpinist, one of the flag bearers of this purist principle, made sure his reputation rests on risk embraced, not avoided. His climbing CV earned multiple Piolet d’Ors, especially since many believed him to be the true successor of the 80s' Polish Ice Warriors. Urubko is best known for his Himalayan firsts: first winter ascent of Makalu (2009) and Gasherbrum II (first winter ascent of any 8000er in the Karakorums, 2011), and daring alpine-style pushes without oxygen. He went on to establish five new routes atop 8000ers until the summer of 2019 finishing with Gasherbrum II.

Denis Urubko on top of Gasherbrum II (2019) via new route. Photo shared by Denis Urubko during the post-summit interview conducted by Dream Wanderlust

Fifty Peaks, Sherpa Excellence & Operational Efficiency

Purja’s approach diverges sharply; between 2019 and 2025, he completed fifty 8,000-meter summits, of which twenty-two were without supplemental oxygen. Many peaks were repeated, and large Sherpa teams facilitated logistics, and pre-fixed ropes to operational mastery. Helicopter transfers between base camps - flying from Dhaulagiri to Kangchenjunga to Makalu - compressed weeks of trekking into hours. Bottled oxygen, which reduces the physiological stress equivalent of several thousand metres, was used consistently, while earlier pioneers had often climbed without.

Purja’s defenders argue that dismissing his climbs as “logistical” is elitist - that in an era of climate change, crowding, and commercialisation. However, the deeper critique is about legacy. Kukuczka’s new routes, Messner’s oxygenless frontiers, Urubko’s winter ascents - these expanded the map of what was possible. Future generations could look at their climbs and imagine new ones. Purja’s 14 Peaks, dazzling as it was, leaves little for others to build on, beyond the realm of logistics and endurance records. Critics argue that such parameters reduce high-altitude climbing to an exercise, where speed and scale overshadow ethical engagement and risk confrontation.

Nirmal Purja on top of Nanga Parbat (2019) Courtesy: Beyond Possible: One Soldier, Fourteen Peaks - My Life in the Death Zone, written by Nirmal Purja

Rethinking Mountaineering Heroism

While Messner championed purity - solo climbs, no oxygen, minimalist style - Purja represents a new archetype: the soldier-athlete with a global platform. Where Kukuczka’s era was about technical firsts, and Hillary’s about national pride, Purja’s achievements live in an age of social media, sponsorships, and documentary storytelling.

Yet socio-cultural context complicates judgment. Purja is Nepalese, emerging from a historically marginalized community in high-altitude climbing. Born in 1983 in Myagdi, Nepal, Purja is now an MBE (Member of the Order of the British Empire), awarded in 2018 for his contribution to high-altitude mountaineering. Purja’s leadership elevates Sherpa climbers, historically invisible despite their central role in Himalayan expeditions. For decades, Western climbers were celebrated as pioneers, while local high-altitude workers carried loads, fixed ropes, and paved the way. Purja’s all-Nepalese K2 winter team in 2021 symbolized a long-awaited shift in narrative - from silent supporters to celebrated leaders.

Media amplification further transforms Purja’s impact. His ascents are global spectacles: Netflix documentaries, Instagram feeds, and press coverage make Himalayan summits shared human events. He occupies a unique position in mountaineering history; both celebrated and critiqued.

And one wonders, can social impact and logistical audacity define new mountaineering heroism, or does classical purist ethos retain moral primacy? With his 50th summit, Purja has already surpassed numerical comparisons with past greats. The question now is less about what mountain he’ll climb, and more about what impact he’ll leave.

Environmental advocacy?

Training the next generation of Nepali climbers? Leading scientific expeditions on glaciers and climate change?

Purja himself has said: “I’m not here to prove anyone wrong. I’m here to show that nothing is impossible.” That mantra has carried him through frostbite, storms, and skepticism. But what does it mean when one man stands on the roof of the world 50 times? For Nepal, it is a reaffirmation that its climbers are no longer footnotes in mountaineering history, but headline figures. For the global audience, it is an invitation to reimagine limits and in a commercial era where Everest base camp resembles a marketplace, his military-style efficiency did showcase what was possible.

But to equate Purja’s 14 Peaks with the pioneering artistry of Messner, Kukuczka, or Urubko is to miss the point. One was a project; the others were revolutions.

Purja’s 14 Peaks is a record - a remarkable one. Kukuczka’s Kangchenjunga in winter, Messner’s oxygenless Everest, Urubko’s Makalu in winter - those are legacies. They changed what the word “possible” meant. Perhaps that is the final measure. As Messner once wrote: “What remains after the summit is the story you tell, and whether it pushes others to dream beyond you.” By that measure, Purja’s tale belongs less to the canon of alpinism and more to the annals of endurance sport.

And maybe that’s enough.

Related Articles

Place your ad here. Call +919163231788 or Contact Us